With the recent news about a baby formula shortage, this is a good time to explain an often-overlooked issue regarding infant nutrition. Many plants, including soy, contain molecules with structures vaguely resembling estradiol. Since estrogen receptors are not very selective1, these compounds can activate estrogen receptor signaling, and are collectively called phyto-estrogens.

For adults and older children this is not a problem, as the levels are irrelevant compared to the body’s normal production of estrogens, and most people don’t get 100% of their diet from soy. However, infants who are fed soy-based formula may be at risk, for two reasons. First, infants are small and many are fed exclusively with formula, so the intake of phyto-estrogens relative to body mass can be quite high. Second, the neonatal period is an important time for reproductive development, and exposure to excess estrogens can cause problems.

So what does the research say?

Biochemically, genistein binds and activates ERα and ERβ estrogen receptors.2 Competition experiments show that relative to 17β-estradiol (the major endogenous estrogen), genistein is 0.7%–4% as strong at binding to ERα and 13–87% as strong at binding to ERβ. In absolute terms, the genistein concentration required for 50% binding was 145 nM for ERα and 8.4 nM for ERβ. In cell culture experiments, 1000 nM of genistein strongly activated an estrogen-responsive luciferase reporter, and indeed the degree of activation was approximately twice as strong as 1000 nM of 17β-estradiol.3

Physiologically, infants fed soy formula have an average serum genistein concentration of 757 ng/mL = 2800 nM, although the variability is high.4 This is approximately 13,000 – 22,000 times higher than the levels of estradiol in infancy, and based on the reporter assay data is clearly enough to activate estrogen receptor signaling. In comparison, breast-fed infants have an average serum genistein concentration of 10.8 ng/mL = 40 nM, which comes from maternal intake.

Mouse studies paint a dire picture. When evaluating these studies, it’s important to check that the dose of genistein is relevant, since many studies use hugely excessive doses. But even the studies using physiologically relevant levels show harmful effects.5 These include uterine developmental defects and cancers,6 abnormal ovarian follicles containing multiple oocytes,7 and inflammation in the Fallopian tubes.8

Importantly, many of these effects are not apparent until the mice undergo puberty, so they could be missed if the studies are stopped before then.

But what about the humans?

You may be shocked to learn that it’s much harder to study humans than mice.9

In particular, reproductive effects generally won’t show up until puberty, and increased risks of uterine fibroids or cancer may not be evident until much later in life. There are also confounding effects because disadvantaged parents are more likely to use formula instead of breastfeeding. (However, among parents who used formula, those who used soy formula tended to have higher income. Maybe it’s associated with veganism.)

But there have been a few studies, most notably the IFED cohort study following infants fed exclusively with either soy or dairy-based formula.10 This found increased maturation in vaginal cells, and larger uterus volume relative to body size, in girls fed with soy relative to dairy. There were no significant effects on estradiol and FSH levels or breast development. No significant effects were found in boys. Interestingly, the study found a high degree of variability in urinary genestein levels in soy-fed infants, ranging from 52 – 102,000 ng/mL (median 9,460 ng/mL). The main limitation here is that the infants were followed only for ~1 year, not through puberty; to my knowledge, there are no prospective studies that did this. Another limitation is that this study was not randomized (though there would be ethical issues with doing this).

Retrospective studies based on self-reported soy formula use have also reported reproductive effects such as increased risk of endometriosis11 and heavy menstrual bleeding,12 and lower age (by ~4 months) of first menstruation.13 I don’t trust these quite as much, though, since self-reporting of infant formula use may not be accurate (keep in mind that self-reporting of diet is already notoriously inaccurate, and parents may not remember what they fed their babies a few decades previously). Furthermore, many of these studies measure several outcomes and don’t correct their significance thresholds for multiple hypothesis testing.

Overall, for a good review of the existing data I would recommend Suen et al. 2021.

So how should we reason about this?

It’s clear epidemiologically that soy formula isn’t causing drastic infertility, but there may be some subtle negative effects, and the levels of genistein exposure are concerning in comparison to the data from cell culture experiments and animal models. The risks are probably greatest for females due to the greater sensitivity of female reproductive tissues to estrogens.

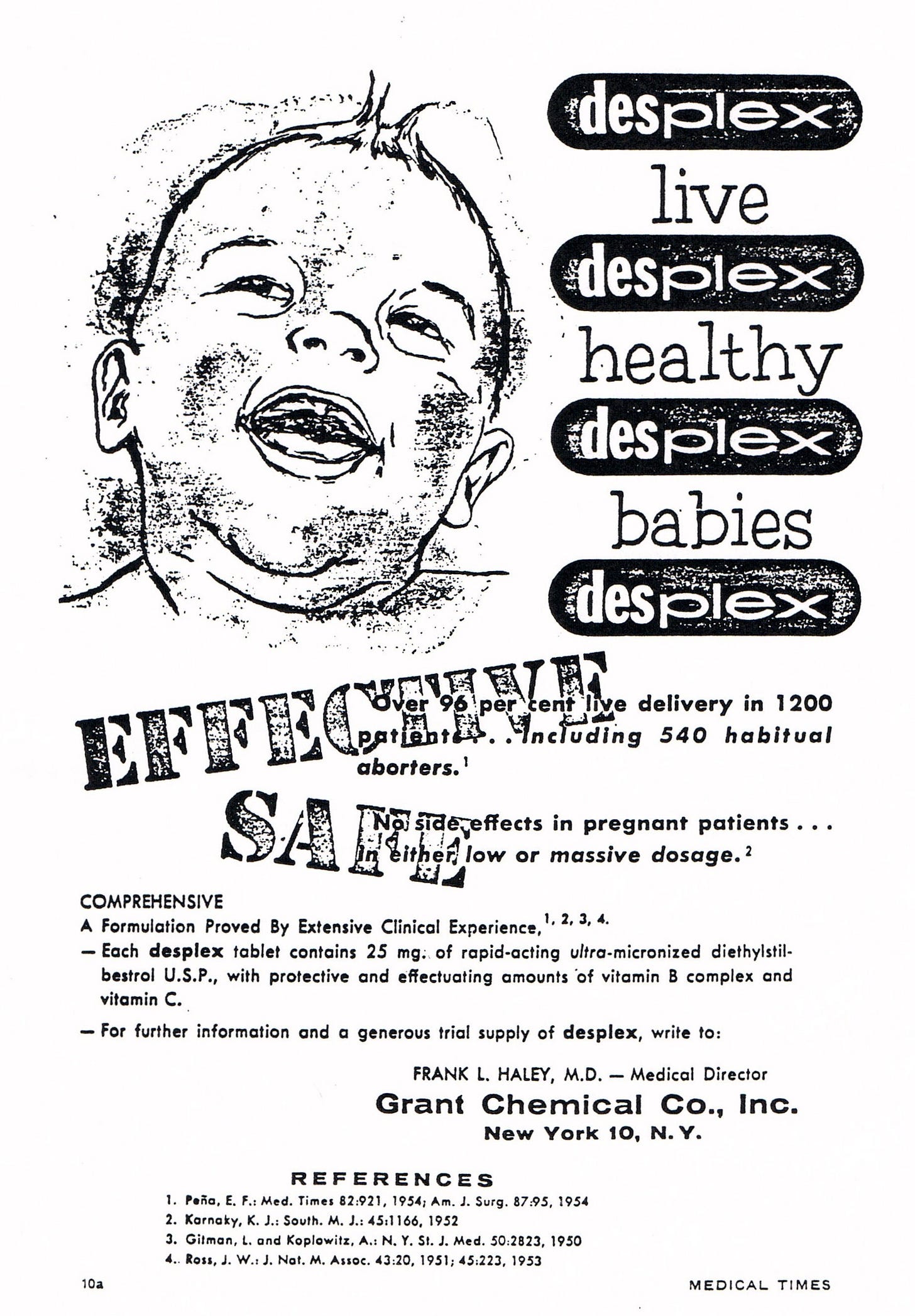

Infants did not have a soy-based diet for most of evolution, so adaptation mechanisms for excess estrogen exposure may not exist. The story of diethylstilbestrol (DES), a synthetic estrogen, may be relevant here.14 From 1938 – 1972 DES was given to pregnant women in an attempt to prevent miscarriages.

However, the excess estrogen caused developmental abnormalities in fetuses, particularly female ones. Women exposed in utero to DES have abnormally shaped uteruses, a higher risk of breast, uterine, and vaginal cancers, as well as of ectopic pregnancies and miscarriages. Men were at risk of cryptorchidism (undescended testes) and epididymal cysts.

Although DES exposure is different from phyto-estrogen exposure in several ways, including dosage and developmental timing, the similarities are concerning enough that I would not be comfortable feeding my infant with soy formula. Genistein is a stronger estrogen than bisphenol A, and plenty of people are worried about BPA.

What is to be done?

Since alternatives to soy formula exist for most infants, I recommend using those. For those who are able, breastfeeding is the best option. Of course, don’t use other people’s breastmilk due to the risk of spreading pathogens.

Soy is not the only source of phyto-estrogens. Similar substances can also be found in many kinds of herbal supplements, so don’t give those to babies.

Furthermore, plastics can leach compounds such as bisphenol A which also have estrogenic effects.15 But based on the typical exposures, I believe that soy infant formula has the greatest potential for risk. Still, I wouldn’t panic about this, and giving your infant soy formula is certainly preferable to letting them starve.

I also think that soy formula should carry a warning label about phyto-estrogen content. The evidence isn’t strong enough to ban it,16 but parents should at least know the risks. This would also give manufacturers an incentive to remove the phyto-estrogens,17 which right now they do not do even though it wouldn’t cost much.

Acknowledgements

I thank Carmen Williams for an excellent presentation on this topic which inspired me to write this post, and giving permission for using her images.

Or, in the words of an anonymous endocrinologist, “the estrogen receptor is a [censored]”. All it takes is a hydrophobic core with hydroxyl groups on both sides, and off it goes.

The degree of activation depends not only on binding but also on the ability of the ligand to induce a conformational change in the receptor.

Dosing is typically by injection but this achieves serum genistein concentrations similar to human infants fed soy formula.

If you are, you’re one of today’s lucky 10,000.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22324503/ This is particularly interesting because the average age of menarche has been steadily decreasing over the past ~100 years.

I also don’t trust the replacements for bisphenol A in “BPA-free” polycarbonates.

Really interesting take on the whole soy thing that I haven't thought before. I wonder if this can be connected to the often noted decrease in age of female puberty: https://vitalrecord.tamhsc.edu/decreasing-age-puberty